A Church with a Rich History and a New Name

Formerly Nolley Memorial United Methodist Church, Nolley Memorial Methodist Church not only has a new name but also a new logo. It depicts an early itinerate preacher on horseback, commonly referred to as a “circuit rider” which has been a symbol deeply rooted in Methodism for many years.

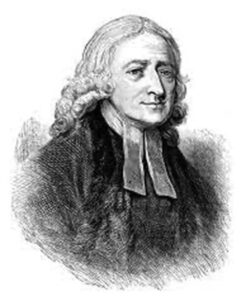

Though the beginning of Nolley Memorial can be traced back to Richmond Nolley’s charge in the Attakapas Circuit, it would be impossible to share Nolley’s history without starting with John Wesley (1703-1791), the Father of Methodism.

John Wesley was an English cleric, theologian and evangelist, who in 1729, at Oxford University in England, led a revival movement within the Anglican Church which came to be known as Methodism.

A group of men met for study, devotional exercises, and charitable work in what they called the Holy Club. John Wesley and his brother, Charles Wesley, are the Holy Club’s most wellknown members. The societies Wesley founded flourished and became the dominant form of the independent Methodist movement that continues today.

In the early 1760s, Methodist layman-preachers traveled to the American colonies. Robert Strawbridge, an Irish immigrant, formed the first Methodist societies in both Maryland and Virginia in 1764.

Although Wesley had not initiated the development of Methodism in the colonies, he welcomed the news of its success, and in 1769, the Methodist founder called for additional volunteers to aid believers in the “wilderness of America.”

In 1771, Francis Asbury came to America and became the American leader of the Methodist movement for over forty years. He was the first bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church (episcopal meaning governed by bishops), which formed in 1784 after an official break from the Anglican Church, propagated by the Revolutionary War.

John Wesley instructed British preachers to enforce Methodist practices in colonial societies. Therefore, early American Methodism was patterned after its English counterpart. Wesley adopted the itinerancy in Britain and the English ministers in America imitated this example of itinerant ministers.

Colonial regions were organized into circuits. The Discipline, a guide for Methodist religious conduct, was effectively enforced. “Without discipline,” Asbury wrote, “we should soon be as a rope of sand, it must be enforced, let who will be displeased.”

The traveling preachers responsible for caring for these societies, or local churches, became known as circuit riders.

Their home was on horseback, carrying their belongings and books in their saddlebags, preaching 25 to 30 sermons and traveling hundreds of miles each month.

The traveling minister in the Methodist Church was noted for his self-sacrificing spirit. They endured terrific hardships in the ministry, which few men of the present age can fathom. They possessed qualities such as courage, tenacity, and unparalleled dedication making arduous and dangerous sacrifices to bring the gospel to the people.

Five hundred of the first 650 Methodist circuit riders retired prematurely from the ministry. Nearly one fourth of the first 800 ministers who died were under the age of thirty-five.

The American Revolution (1775 – 1783) strained the relationship between American Methodists and the Anglican Church. In Britain, Methodism was a lay movement within the established Anglican Church. But war with the British severed all political and ecclesiastical ties that had existed between England and her colonies. The idea of religious liberty developed in the minds of Americans during the conflict.

These developments terminated the relationship between the Anglican Church and governments in the new nation, thus, Wesley’s establishment of a separate Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States.

Methodism spread across the young country during the early national period because of the ministry of the traveling preacher. The Methodist Church was a well-organized unit in the 35 United States.

Bishops directed hundreds of preachers across the continent. Itinerants and Methodist administrators met in general conferences, annual conferences and quarterly conferences. The circuit system and its component part the traveling minister – distinguished the early American Methodist Episcopal Church.

The itinerant preachers journeyed in every conceivable type of conditions to reach Methodist gatherings on time, including maneuvering during war times between American and British Patriots and Indian uprisings.

The winter season increased the preacher’s problems, with constant exposure and epidemics leading to serious ill health. Many times, roads and bridges were nonexistent.

It sometimes happened that a minister was treated with contempt by an entire community and was denied entrance.

Richmond Nolley, the namesake of Nolley Memorial Methodist Church, was the first Methodist Episcopal circuit rider martyred in Louisiana.

While braving the wilds of early Louisiana, he died traveling to his next service near present day Jena.

Though born in Virginia in 1784, Richmond Nolley moved to Georgia as a young boy with his parents. Sadly thereafter, he was orphaned. With nowhere to go, John Lucas, a Methodist leader in Sparta, Georgia, gave him a clerk job at his store and a place to live.

In 1806, Richmond attended a camp meeting (revival) near Sparta and was converted at the young age of 22 by the fiery young Reverend Lovick Pierce.

Richmond lived at the Lucas’ for another year, encouraging those in the area and preparing for the ministry. In 1807, he was admitted into the Conference and was appointed to preach on the Edisto Circuit. In the following years, he served in Wilmington, Charleston, Washington and Tennessee.

His ministry was no easy task – he even became accustomed to people throwing firecrackers at him while he was in the pulpit. He undertook the practice of kneeling with his eyes shut to pray and continue. It was said that he spoke with great energy, his voice a trumpet.

In 1812, amidst the War of 1812, Richmond Nolley and three other preachers headed west. He went on a mission to Tombigbee, in the territory of Alabama. There he devoted two years of hard labor, filling his appointments with fidelity, though often walking on foot with his saddlebags upon his shoulders from house to house.

Nolley was known to be intelligent, full of commitment and courage in his ministry.

After two years in Alabama, he was sent to the Attakapas circuit, which included all Southern Louisiana and parts of Mississippi. He would receive no easy appointment there either.

As historical documents relate, he went without a murmur to face the danger and hardships which are to be found in the wilderness, badly paved to no roads, deep waters to cross, flies and mosquitoes, intense heat of the summer and the mud and mire of the winter months.

A sugar planter once drove him away from his smokestack, where he craved only to warm himself. It is also recorded that so called “evildoers” took him out of the pulpit at St. Martinville, as to dunk him in Bayou Teche when a courageous black woman vigorously assailed them armed only with a hoe and rescued Nolley.

At the 1814 Mississippi Annual Conference, Nolley was reappointed to the same circuit, Attakapas. Membership had increased by 33% during his ministry; he was effective.

On what would be Nolley’s last mission, he decided to proceed toward Jena from Sicily Island, despite the cold and rainy weather.

On Friday, November 25, 1814, Nolley came to an Indian village.

He suspected that Ford’s Creek, a branch of “Hemps Creek” up ahead would be difficult to cross, so he hired an Indian to assist him. He wanted to cross the creek, located northeast of Jena, before it got too late, else he would have to delay further and stay with the Indians, losing even more time reaching his destination.

He left his saddlebags, valise and some books with his Indian guide. He mounted his horse and attempted to ride through the creek.

The current was swift and they were soon beyond the landing place on the opposite shore and could not climb up the steep bank. The rider and horse were separated.

The horse went back to the Indian while Nolley was able to grab a tree limb and climb up the opposite bank. Nolley yelled to the Indian on the opposite bank that he would walk to a Mr. Carter’s house a couple of miles distance and asked the Indian to keep his horse until the next day. Cold, wet and physically exhausted, he was able to travel about one mile.

The next day, when the creek had subsided, the Indian crossed over. He found the preacher’s coat on the ground. Just ahead he found Nolley, with his eyes neatly closed, his left hand on his breast, his right hand fallen to the side, nestled beneath a big pine tree.

From his muddy knees and the prints on the ground, it was clear that he spent his last moments on his knees in prayer. (Legend says that he succumbed to death in the vicinity of present- day East Baker Street.)

His body was taken to the nearby house. The date was November 26, 1814. Mrs. Pol- ly Francis told the story for many years of how she made his shroud and Mr. Young hammered out the nails and a coffin was built. A board with the initials “R.N.” was nailed to the tree where his body was found.

On the following Sunday afternoon, he was buried in Catahoula Parish, now LaSalle Parish, near the Pentecost Family Cemetery east of Jena. In 1879, the Louisiana Conference placed a monument at the approximate place of his death.

In 1910, the small obelisk monument was moved to the cemetery behind Nolley Methodist Church, where it stands today.

On October 24, 1952, Richmond Nolley’s remains were moved to the front lawn of the church where a large granite slab monument honors his legacy and recounts his story. Visitors are welcome to view his final resting place, which the United Methodist Church marked as Historic Site No. 42, the first United Methodist historical site in Louisiana.

The name of Richmond Nolley lives on in the heritage of the people in both Alabama and Louisiana. His devotion to the ministry and his Lord remains an example to Methodists of all ages. He became Louisiana’s first Methodist martyr, at the young age of 30 after only 8 years of ministry.

The Hemphill Creek Congregation was formed in the late 1700’s or early 1800’s, shortly after Spanish land grants were made to Isaiah Slater, Thomas Doggett, Charles McBride and Matthew Stone.

Some of the families in the early local church included, John Doyle, Elias Carter, Matthew Wilson, Henry Kiper, Uriah Vincent Whatley and William Henderson Turnley, as well as additional names noted in the records, such as: Breithaupt, Forsythe, Coleman, Boddie, Hopkins, Kendrick, Baker, Roberts, Pentacost, Blackman, Butler, Barr, Bobbitt, Anders, Drewett, Warner, Walker, Long, Davis, Yancy, Bennett, Thompson, Coon, Honeycutt, Wade, Allen, Sheppard, Bradford, Warwick and many others.

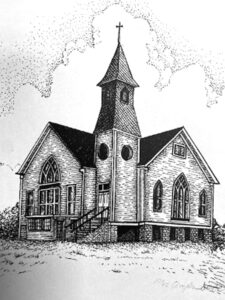

The first church building, reportedly made of logs and called Hemps Creek Methodist Episcopal Church, was erected on the east bank of Hemphill Creek just north of the main road at the time in what is known as Old Jena.

This was just under the hill from the Cannon family residence, which is now part of Ellen Henry’s yard, Nolley’s destination to preach to the brethren. Across the road was the parsonage and just behind, the present-day Bellevue Baptist Church was the Jena Seminary.

A new building was constructed in 1895 due to the flooding in the creek bottom. The building was in Old Jena on land donated by Dr. B. L. Thompson, father of Mrs. Louise Cobb. A contract was entered into with Jim Coleman, father of Mrs. Sena Honeycutt, Edgar Coleman and Dr. J.A. Coleman, to furnish the materials and direct the construction of the new building.

As the congregation grew, approximately 1 and 1/2 acres of land was acquired from R.M. Renfrow in 1910.

In 1911, an additional 3 acres were acquired from Mr. Buchanan and the L & A Railroad. A new church was constructed in 1911 in the area of the present-day parking lot of Nolley Methodist Church in Jena, on Highway 84.

In 1949, the congregation moved into the present-day structure renamed “Nolley Memorial Methodist Church.” In 1952, the remains of Richmond Nolley were moved to the church’s front lawn.

The name Nolley Memorial United Methodist Church was adopted in 1968 to coincide with the merging of the Methodist Episcopal Church with the Evangelical United Brethren Church.

Today we are Nolley Memorial Methodist Church and invite you to join us. All are welcome to attend worship on Sundays at 10:30 or bring your children, grades K-12, to our “Wednesday After School” activities. If you are searching for a church home, we would love to have you visit us at Nolley.

Nolley Memorial has seen years of ministry and has a history rooted in the dedication and faith of its pastors and believers. Though our name and logo may have changed, just like Richmond Nolley and many other heroes of our faith, our commitment to worship, the study of scriptures and determination to bring the gospel to the people has not changed.